SIMD - Vector Primitives and Operations

For quite a while, all major CPU architectures have included support for SIMD instruction sets. Consequently, system programming languages are now beginning to offer support for SIMD, either through libraries or as first-class language primitives. SIMD provides an optimization window for modern software through data parallelism, greatly accelerating computation. This article aims to provide a detailed overview of SIMD vector primitives and operations supported by modern languages, along with some real-world examples.

SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data)

SIMD stands for Single Instruction Multiple Data, which basically boils down to applying the same operation on multiple data or an array of primitives (such as integers, floats, or boolean masks). Let’s explore this concept deeper with an example.

Consider a mathematical vector with four components. If we want to perform element-wise addition of these vectors, it requires four separate addition operations.

let v1: [f32; 4] = [1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0];

let v2: [f32; 4] = [5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0];

let add: [f32; 4] = [

v1[0] + v2[0],

v1[1] + v2[1],

v1[2] + v2[2],

v1[3] + v2[3],

];

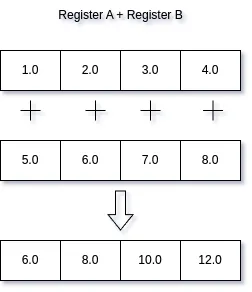

In the example, we’re performing element-wise addition on two float arrays. Imagine if there were native support for directly adding float arrays like this. That’s exactly what SIMD provides: the ability to execute a single operation, such as addition in our case, on multiple values, like two float arrays with 4 elements each.

use std::simd::f32x4;

//....

let v1 = f32x4::from_array([1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0]);

let v2 = f32x4::from_array([5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0]);

let add = v1 + v2;

This is a SIMD version of our example. In SIMD addition of two vectors, multiple operations are combined into a single one. There are no loops under the hood, as long as the target CPU supports SIMD. We’re essentially applying the same operation on multiple data in parallel, which is simply known as data-level parallelism. Instead of four separate add operations, we’re adding four numbers in parallel. This can significantly improve performance in software that deals with a lot of calculation or processing sequential data.

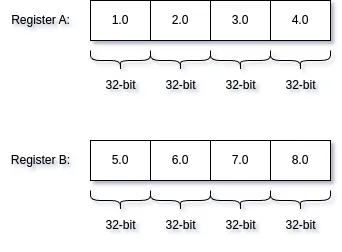

Vector Registers

SIMD operations are backed by vector registers, which are registers capable of holding 128, 256 or even 512 bits of data. We have the ability to perform operations on these registers, such as our example above, where we use two 128-bit registers to add two arrays of 32-bit floats.

Modern system programming languages provide support for these registers through vector primitives or structs such as f32x4 in Rust, @Vector in Zig, and std::native_simd<float> in C++.

For documentation on SIMD support in each of these languages, you can follow the hyperlinks:

Rust, Zig, C++.

These vector registers also support 64-bit floating-point and integer data types, as well as boolean masks ranging from 8-bit to 64-bit per element.

CPU Support

Not all CPUs support vector registers, especially the larger ones like 512-bit. However, all widely used CPU architectures do support 128-bit vector registers, making it important for programmers to be aware of their availability and utilize them effectively. In this article we’ll mainly work with 128-bit register as they are widely supported. Here are the documentations for 128-bit SIMD support on various architectures:

Vector Operations

Let’s go through some of the fundamental operations you can perform with these vector registers:

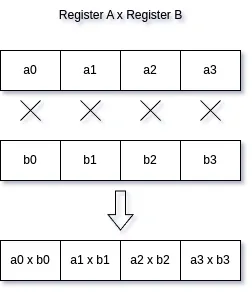

Arithmetic

These don’t need any explanation; they are just your old regular arithmetic operations. The only difference being, in the case of SIMD vectors, they’re element-wise operations. So, if you multiply, add, divide, or subtract two SIMD vectors, the operations will be done element-wise. Here’s a simple diagram for multiplication; all other operations work the same way.

Comparison, Logical and Masks

Like regular primitives, SIMD vectors also support logical (AND, OR, NOT, XOR) and comparison (EQUAL, LESS, GREATER) operations. However, they work slightly differently because we’re operating on multiple values simultaneously.

The comparison operation returns a packed bitmask, where four 32-bit masks are packed into a single 128-bit SIMD vector. Each mask contains all 1’s for true and all 0’s for false. For example, SIMD A > B essentially boils down to the following pseudo code. Additionally, it’s worth noting that these masks are stored and represented as a set of integers (four 32-bit ints in our example).

A = [a0, a1, a2, a3]

B = [b0, b1, b2, b3]

// M = A > B

Mask = [

(a0 > b0) ? 0xFFFFFFFF : 0x00000000,

(a1 > b1) ? 0xFFFFFFFF : 0x00000000,

(a2 > b2) ? 0xFFFFFFFF : 0x00000000,

(a3 > b3) ? 0xFFFFFFFF : 0x00000000,

]

The logical operations like arithmetic are applied element wise.

A = [a0, a1, a2, a3]

B = [b0, b1, b2, b3]

// M = B | A

M = [

a0 | b0,

a1 | b1,

a2 | b2,

a3 | b3,

]

Data Movement

Data movement involves swizzling or shuffling, where you can create a new SIMD vector by combining two input vectors based on a user-defined mask. For example:

A = [a0, a1, a2, a3]

B = [b0, b1, b2, b3]

R = shuffle(A, B, [0, 1, 6, 7]) // M = [a0, a1, b2, b3]

Here, we are copying the first two elements (a0, a1) from A and the last two elements (b2, b3) from B based on our mask [0, 1, 6, 7]. The mask is represented by an array of indices from the concatenation of A and B, i.e. [a0, a1, a2, a3, b0, b1, b2, b3].

The representation of the mask differs based on the programming language and its SIMD library. Rust uses concatenated array indices for masks, while Zig uses positive indices to select elements from the first input and negative indices to select elements from the second input.

Rust example, rust uses the term swizzle for data movement operation. Rust Docs

let v1 = f32x4::from_array([1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0]);

let v2 = f32x4::from_array([5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0]);

let m: f32x4 = simd_swizzle!(v1, v2, [0, 1, 6, 7]); // m = [1.0, 2.0, 7.0, 8.0]

Zig example, zig uses negative indices for masks. Zig Docs

const v1 = @Vector(4, f32){1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0};

const v2 = @Vector(4, f32){5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0};

const m = @shuffle(v1, v2, [_]i32{0, 1, -3, -4}); // m = [1.0, 2.0, 7.0, 6.0]

You can also rearrange the order of elements in a SIMD vector using shuffle/swizzle operations.

use std::simd::f32x4;

use std::simd::simd_swizzle;

// ...

let v1 = f32x4::from_array([1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0]);

let v2 = simd_swizzle!(v1, v1, [3, 0, 2, 1]); // v2 = [4.0, 1.0, 3.0, 2.0]

Reduction

Until now, all the vector operations we explored were mostly element-wise operations on two input vectors, known as vertical operations. Another type of operation we can perform is among the elements in the same SIMD vector, known as horizontal operation. For example, adding all elements to a single 32-bit float value, i.e., reducing to a single value.

A = [a0, a1, a2, a3];

r = a0 + a1 + a2 + a3 ; // reduce sum

All three languages offer macros or helper functions for reduction.

Rust example, Rust Docs

use std::simd::f32x4;

use std::simd::num::SimdFloat;

//....

let v1 = f32x4::from_array([1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0]);

let sum = v1.reduce_sum(); // 10

Zig example, Zig Docs

const v1 = @Vector(4, f32){1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0};

const sum = @reduce(.Add, v1); // 10

Practical Examples

Now, let’s explore some practical use cases for these SIMD vectors and operations we’ve just covered.

Dot Product

The dot product is a mathematical operation on vectors that involves element-wise multiplication followed by the summation of the elements of the multiplication result.

let v1 = f32x4::from_array([1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0]);

let v2 = f32x4::from_array([-1.0, -2.0, -3.0, -4.0]);

let dot_product = (v1 * v2).reduce_sum();

Similarly, SIMD can be applied to other linear algebra operations such as matrix multiplication, transposition, decomposition, etc. Vectors and matrices are widely used in computer graphics and image processing, making SIMD essential for accelerating computation in these areas

Sarrus Rule

Sarrus rule is another mathematical operation often used to calculate the determinant of a 3x3 matrix or the cross product of two 3D vectors.

// 3x3 matrix, assuming the 4th component to be zero

fn determinant(mat: [f32x4; 3]) -> f32 {

let m0 = mat[0]

* simd_swizzle!(mat[1], [1, 2, 0, 3])

* simd_swizzle!(mat[2], [2, 0, 1, 3]);

let m1 = simd_swizzle!(mat[0], [1, 0, 2, 3])

* simd_swizzle!(mat[1], [0, 2, 1, 3])

* simd_swizzle!(mat[2], [2, 1, 0, 3]);

return (m0 - m1).reduce_sum();

}

// Assuming the 4th element to be 0 for both a and b

fn cross(a: f32x4, b: f32x4) -> f32x4 {

let temp0 = simd_swizzle!(a, [1, 2, 0, 3]);

let temp1 = simd_swizzle!(b, [1, 2, 0, 3]);

let temp2 = simd_swizzle!(a, [2, 0, 1, 3]);

let temp3 = simd_swizzle!(b, [2, 0, 1, 3]);

return (temp0 * temp3) - (temp2 * temp1);

}

String Search

At this point, it’s pretty clear that SIMD can be effectively utilized to optimize mathematical calculations. But what about other use cases? Another area where SIMD has proven its effectiveness is in parsing data. SIMD can significantly speed up something like JSON parsing. Take a look at the benchmark on simdjson.

Let’s return to our string search example. When searching for a substring in a lengthy text, we can leverage SIMD vectors to compare multiple bytes simultaneously, allowing us to implement more efficient string searching algorithms.

// Assuming the string are ASCII 8-bit each

pub fn contains_substr(text: &str, substr: &str) -> bool {

if substr.is_empty() || substr.len() > text.len() {

return false;

} else {

let substr_bytes = substr.as_bytes();

let substr_len = substr_bytes.len();

let first_char = substr_bytes[0];

let last_char = substr_bytes[substr_len - 1];

// fingerprint from first and last character of the substring

let first_fing = u8x16::splat(first_char.try_into().unwrap());

let last_fing = u8x16::splat(last_char.try_into().unwrap());

// create 16-byte chunks for figerprint checks

let text_bytes = pad_text(text.as_bytes(), substr_len);

let total_chunks = text_bytes.len() / 16;

for (i, chunk) in text_bytes.chunks(16).enumerate().take(total_chunks) {

// blocks to compare fingerprints with

let first_block = u8x16::from_slice(chunk);

// second_block start from start + offset where offset = substr_len - 1

let sb_start = (i * 16) + substr_len - 1;

let second_block = u8x16::from_slice(&text_bytes[sb_start..sb_start + 16]);

let eq_a = first_block.simd_eq(first_fing);

let eq_b = last_fing.simd_eq(second_block);

let mut mask = eq_a & eq_b;

// fingerprint match

while mask.any() {

// actual comparison, we can replace this with SIMD aswell but this should be

// trivial enough for compiler optimization

let set_index = mask.first_set().unwrap();

let f = set_index + (i * 16) + 1;

if text_bytes[f..f + substr_len - 2] == substr_bytes[1..substr_len - 1] {

return true;

}

// f - 1 starting index of substring in the text

mask.set(set_index, false);

}

}

return false;

}

}

// Padding could be done in a better way

fn pad_text(data: &[u8], substr_len: usize) -> Vec<u8> {

// Determine the padding needed

let padding_needed = (16 - (data.len() % 16)) % 16 + substr_len - 1;

let mut padded_data = Vec::with_capacity(data.len() + padding_needed);

padded_data.extend_from_slice(data);

padded_data.resize(data.len() + padding_needed, b'\0');

padded_data

}

This sub-string search example is based on SIMD-friendly Rabin-Karp modification. While I haven’t benchmarked the algorithm myself, the referenced article does contain benchmarks demonstrating its effectiveness.

Auto Vectorization

Auto vectorization is a compiler optimization technique where the compiler automatically vectorizes array operations to some extent. While it’s generally beneficial to let the compiler handle most optimization tasks, auto vectorization doesn’t always yield the desired outcome, particularly in cases where vectorization is nontrivial. In such situations, you may need to manually write your own vectorized code. This is where the support for SIMD in modern languages truly shines, offering developers the flexibility to optimize performance-critical code.

Wrap-up

Vector primitives are incredibly powerful tools for speeding up computations. System programming languages are now incorporating support for them, whether through libraries or as first-class language features. This support gives developers the ability to leverage SIMD technology in a more portable manner, enabling us to write more efficient software.

Hey, you made it to the end! You might want to check out a linear algebra library I recently wrote in Zig called zig_matrix. I’m extensively using Zig’s @Vector SIMD support in my implementation of some of the most widely known and utilized linear algebra operations. Feel free to email me with any feedback or questions!